Mr. Coker’s title suggests action. Or a photograph.

Improvising. Here are two definitions.1 The first is to make something with little preparation. The second is to make something from available materials. Perhaps a way to combine these in reference to musical practice is to say: Assuming prior exploration, knowledge, and deep understanding of materials make something out of these materials with little preparation. So on the one hand the field of materials is defined, but “with little preparation” imparts the notion that the practice is to make something new out of the familiar.

Jazz. What the heck does jazz do anyway?

To paraphrase EM Forster from his lectures on “Aspects of the Novel”2 –

“If you ask one type of man ‘what does jazz do?’ ‘Well—I don’t know— seems a funny question to ask— jazz’s jazz — I suppose it kind of tells a story— so to speak.’ He is quite good tempered and vague, and probably driving a motor-bus at the same time and paying no more attention to jazz than it merits. Another man, whom I visualize as on a golf course, will be aggressive and brisk. He will reply: ‘What does jazz do? Why tell a story of course, and I’ve no use for it if it doesn’t.”

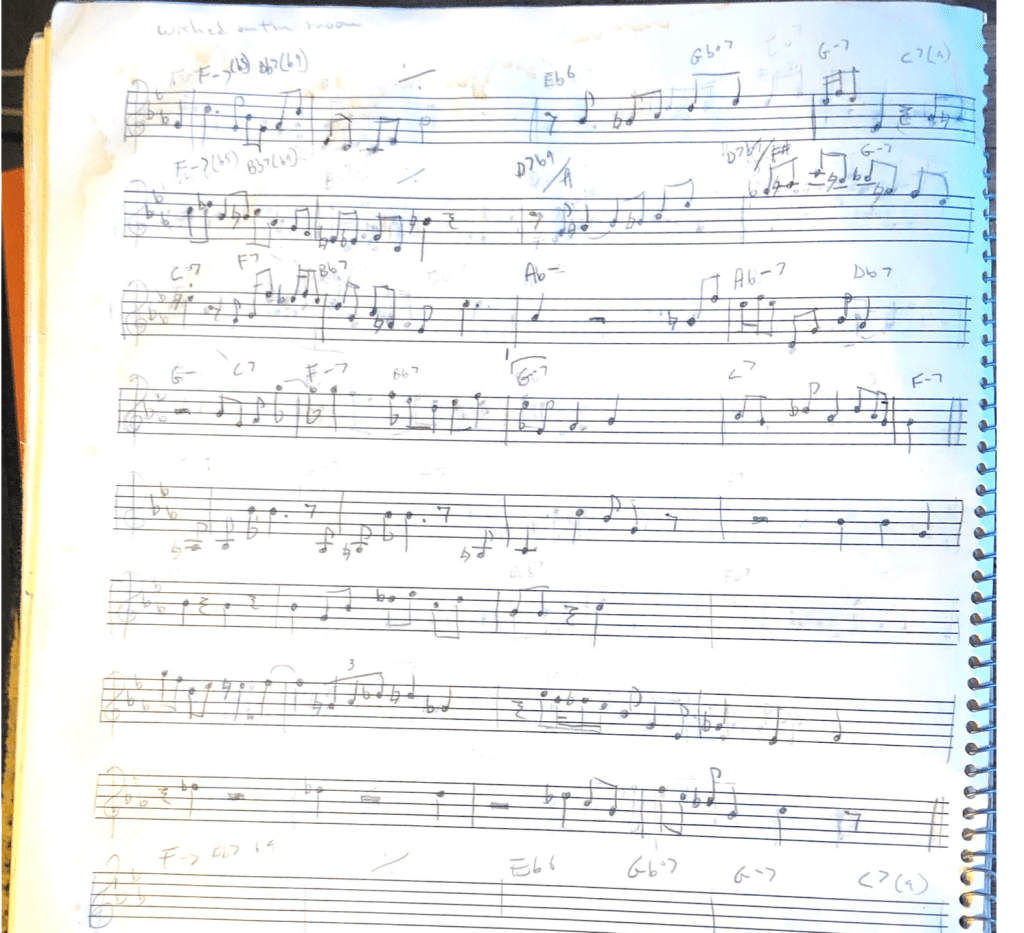

I was introduced to Jerry Coker’s Improvising Jazz by Billy Novick3, clarinetist and saxophonist, arranger and composer. I forget how I came to take lessons from him. I played the five-string banjo. I learned a lot but my instrumental chops needed more work than I knew how to give. This was in 1979-80. Each lesson Billy would give me a solo to transcribe. “I Can Dream Can’t I?” ; “Solar” ; “Tin Tin Deo” ; “Night in Tunisia” ; “Without a Song” ; “You Are Too Beautiful” ; “I Wished on the Moon” ; “The Man I Love” ; “The End of a Love Affair” ; “Liza” ; “O Grande Amor”; “I Only Have Eyes for You”; “ I Told You So”. It was exhausting! A couple of months was all I could take. For all my effort what remains are partial transcriptions and the book Improvising Jazz.

So here is what Mr. Coker did. First chapter: Introduction to Melody. Second chapter: the Rhythm Section. Third chapter: the First Playing Session. Fourth chapter: Development of the Ear. These chapters are followed by further study of chord types, swing, the diminished scale, a little more shedding on melody, and chord superimposition. He closed the technical study with an examination of chord substitutions based on functional harmony.

Simple materials to spontaneously make new. Added are four appendices. Appendix “A” is titled “Aesthetic Criteria for the Evaluation of a Jazz Artist.”Appendix B outlines the issue of “harmonic coordination of the piano player’s left hand with the bass player’s lines.” Mr Coker gives for the piano player “Some Possibilities for Voicings” in order to separate and clarify the two instruments. Appendix C gives alternate chord progressions, common turnarounds, and other examples. Appendix D closes out the book with 26 pages of “Tunes, Categorized According to their Characteristic Progressions.”

Practical and concise. It reads like a bus driver’s safety and repair manual. And, yes, there are homework assignments for every chapter. What did you expect?

Mr Coker maps out a wonderful definition:

“Jazz music, with its roots in basic rhythms and simple melodies, has developed naturally into a blend of musicianship, humanity, and intellect…” 5

He calls it by its full name, “jazz music.” He doesn’t set it apart into some other special place. It’s not highfalutin, it’s not lowfalutin. His concern is rhythm and melody. Harmony, dynamics, and timbre are happening too, but they’re like the wait staff, the sous chef, the florist. Necessary, yes, but not the bride and groom. Because in jazz music, Melody marries Rhythm.

Then there’s that word naturally. Mr Coker doesn’t mean it in the sense of without a doubt, like it was foretold. Nor does he mean it in the sense of being expected or conforming or accepted. Mr Coker means naturally in the sense of happening with spontaneity. Jazz music is a practice freed from artificiality, affectation, or inhibition.

And finally Mr Coker caps it off by saying that jazz music requires musicianship, for sure, intellect, absolutely necessary, and most profound— humanity. Jazz music is made by people whose lives are embedded in the music itself at the moment of creation.

This begs the question— can one be a virtuoso musician and intellectual genius and constitute a deep player of jazz music? By Mr Coker’s definition, the answer is NO. To be a complete player one must bring their own life experience to the work.

Were there any actual practitioners of jazz music that I had first-hand experience with that would confirm Mr Coker’s definition?

When I was at Wesleyan University getting an MA in Music, ( 1989-91) Professor Anthony Braxton, McArthur Grant recipient, was my “advisor” the 2nd year.

In one of our infrequent meetings he told me that he decided to become a virtuoso on saxophone because it would be “convenient” to have that level of skill on the instrument. I don’t believe that was as easy for him as he made it sound! I think what he was referring to was that physical proficiency was nothing more than a baseline. Playing by ear, sight-reading, and finger dexterity were the means by which the story gets told, not the story itself.

I have a copy of the first volume of his Tri-Axium writings. In my humble opinion, I’d say Prof Braxton covers the ‘intellect’ part of Mr Coker’s definition quite well.

Then for the human part. Professor Braxton spoke to two points on that critical issue.

His view on virtuosity was that it served as a deep skill-set that was important to him, but he passed no judgement as to what anyone else did.

And in what was supposed to be a typical theoretical post-graduate music discussion, while standing in the waiting room to the music department housed in that concrete coffin-like campus building right out of the Brutalist tradition, I remember Professor Braxton stamping his foot and shaking his professorial fist proclaiming “I make instantaneous decisions based on the emotional context of the moment!”

Seems Mr Coker, way back in 1964, came up with a pretty good definition of jazz music.

In one of my lessons with Mr. Novick he said the following in as much as an afterthought really, something that he didn’t know was actually “true” in some sociologic sense, but that it was how he thought about this music that he loved so much. While I was packing up my 5-string for the day, he said ( referring to the music of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie ) “I think the way this music came about was because they were black and no cared who they were or what they did, and because no one was listening, they were free to invent whatever they wanted.”

Improvising Jazz makes no pronouncements as to who you are supposed to be.

Improvising Jazz concentrates on expressing who you are in the moment.

All packed into 115 pages. A good place to begin.

Foot notes:

- American Heritage Dictionary 5th Edition

- E.M. Forster “Aspects of the Novel” Harcourt, Inc. London 1927; 1955 page 25

- Billy Novick http://billynovick.com/

- “I Wished on the Moon” Music Ralph Rainger Lyrics Dorothy Parker. Billie Holiday 1935 Teddy Wilson and His Orchestra, the Ben Webster solo https://open.spotify.com/track/7cbfKO5rp9BkGRpTs0uuY3?si=8be702b69ade4bce

- from Mr Coker’s Introduction