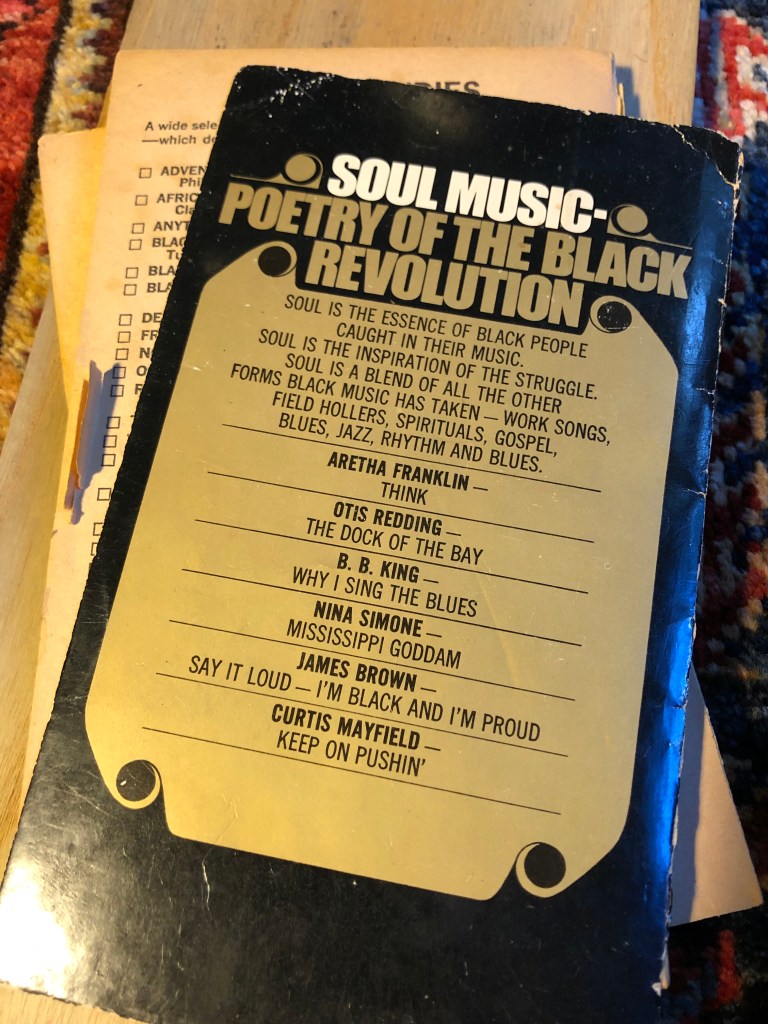

The Poetry of Soul edited by A.X. Nicholas

Bantam Books 1971

A collection of songs chosen by Mr. Nicholas to demonstrate “the Black experience as perceived— as lived.” It is notable that, back in 1971, he capitalized the word Black, a practice which has now, in 2021, fifty years later, become part of the current lexicon, in magazines such as The New Yorker.

The “song-poems” ( as he identifies them ) are divided into four groups—

“1. Black World as Passion

2. Black World as Pain

3. Black World as Protest

4. Black World as Celebration”

Mr. Nicholas speaks from a viewpoint common to that period — “Soul music is the expression of the Black man’s [my italics] condition…” He speaks of “Amerika.” He states “…Black culture is basically a defense against the dominance of white culture.” In a ten page introduction he lays out the history, beginning with a James Weldon Johnson quote that in itself begins with “In 1619…” A reference that found its voice in 2019 1. Nicholas follows this passage with the “double meaning” of spirituals used to guide enslaved people moving on the Underground Railroad. See Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad (2016). Mr. Nicholas follows with “During and after World War I, there were mass migrations of Blacks from the agrarian South to the industrial North— the endless trek… to Detroit auto industry, to Chicago packing houses…” See The Warmth of Other Suns Isabel Wilkerson, (2010).

Within a few short pages Mr Nicholas maps out the scholarship and themes of the Black experience to be elucidated in song, film, art, non-fiction and fiction from before 1971, the year The Poetry of Soul was published, right up to the present. And one can argue that the example of mapping out common repeating problems and situations is in itself a theme in the history of Black people in Amerika.

Mr. Nicholas then follows with an equally brief but detailed history of genres invented by African-Americans that have been so fundamental to the sound of American music. In going through the songs I was curious about what happened to the writers and participants in the making of these songs? In a People magazine standing-in-line-at-the-market way— what are they doing now?

Here are a few of the stories from this wonderful little compendium of songs gathered by one individual in 1971.

Johnny Taylor “Love Bones”

Interesting that Johnny Taylor’s version is NOT on Spotify. You can read his biography on Wiki. DJ, songwriter, businessman, father. Grammy Award nominations in 1969, 1977 and 2001. He should get a posthumous Grammy Award just for that.

Bettye LaVette “He Made a Woman Out of Me”

Fred Burch and Don Hill own the rights to the song. Fred Burch with others wrote songs covered by the likes of Patsy Cline, Elvis, and Paul McCartney. Can’t forget Bobbi Gentry who also recorded “He Made a Woman Out of Me”.

The single, recorded in 1969. According to one source, went to Billboard #25 ( R&B). Banned by some stations due to risqué content.2 You can read Bettye LaVette’s story on Wiki. Once again, a great human being. Spelled B-E-T-T-Y-E. Still going strong– http://www.bettyelavette.com/

Aretha Franklin “I Never Loved a Man ( The Way I Love You )”

Written by Ronnie Shannon specifically for Ms. Franklin, the song is a marker, an icon, a talisman for the state of race relations in the history of popular-music making. ( If I do say so myself!) Here is a tune about a woman idolizing a no-good lover man, written by a man, just the kind of theme Billie Holiday made famous. Oh but how times have changed since 1971! The version above plays like a celebration.

In the original Ms. Franklin was backed by the Muscle Shoals rhythm section— white session players who cannot be mentioned without using the word “legendary”3 –– who also co-owned the studio itself. In other words, they not only were studio players, they were owners. This is something to be proud of, to be sure, and, although they didn’t own the record companies or the radio stations or necessarily the publishing rights, they received a steady income based not only on their music chops, but on the dignity of ownership. Now I don’t want to get all serious and nay-saying and what-all but hear me out.

In an interview on NPR many years ago (1990’s so don’t hold me to this), an African-American businessman ( I believe from Mississippi ) made the point that a bank would be happy to lend $20,000 to a black man to buy a Cadillac but not to start a business. So along with creating the defining of Aretha’s sound, of which she was extremely demanding, these white players got those business loans far easier than their African-American counterparts.

To quote President Obama when he was still a Senator—

“Legalized discrimination – where… loans were not granted to African American business owners,… helps explain the wealth and income gap between black and white,…” 4

I digress, although perhaps Mr. Nicholas would appreciate the effort.

The Poetry of Soul is an earnest document both in the simplicity of its presentation and in the complexity of the material it presents. Today poetry itself has been on a long journey through spoken word and rap resulting in a young poet laureate speaking at the inauguration. But, speaking from the vantage point fifty years later, in spite of the connection to the poetical nature of song lyrics, the idea that the lyrics to any song in this edition were written by a single person in quiet contemplation, as one imagines a poem to be created, really doesn’t do justice to the task of song writing. I think these songs were more like created in nondescript crucibles housing sound-deadened rooms filled with cool instruments and hot people: songs born out of a dynamic entity made in concert with others.

A.X.Nicholas doesn’t have much of a search engine footprint. Out of all the writers, singers, sidemen, those women who sang harmony and backup5 , groups, bands, soloists, headliners, producers, studios, and all the other personalities, historical figures, and any other righteous people unmentioned in this small but significant collection, it is the story of editor himself, one A.X. Nicholas, that remains most Delphic.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/podcasts/1619-podcast.html

- https://secondhandsongs.com/performance/235812

- On Franklin’s session were the Muscle Shoals rhythm section: drummer Roger Hawkins, organist Spooner Oldham, guitarists Jimmy Johnson, and Memphis session players bassist Tommy Cogbill and Chips Moman on lead guitar.

- page 132, “THE SHADOW OF CREDIT: The historical origins of racial predatory lending and its impact upon African American wealth accumulation” Charles Lewis Nier III; University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change Vol II 2007-2008 .pdf

- see Oscar winning “20 feet from Stardom” 2013