I attended Wesleyan University 1989-91. I was enrolled in the Music MA program, not under ethnomusicology, but rather a loosely defined performance/composition designation. I never really understood what that meant, but it didn’t much matter because it was the ethno students who had the pressure on them to perform, class-wise, not me. Also, since it was an unusually large group – eleven students – I was the runt of the litter so to speak, as the rest of them were on the ethno track. This turned out to be just fine. I could experience the Wesleyan experience without expectations of anyone expecting anything extra from me. Which had its down side, in that I wasn’t expected to be a part of anything.

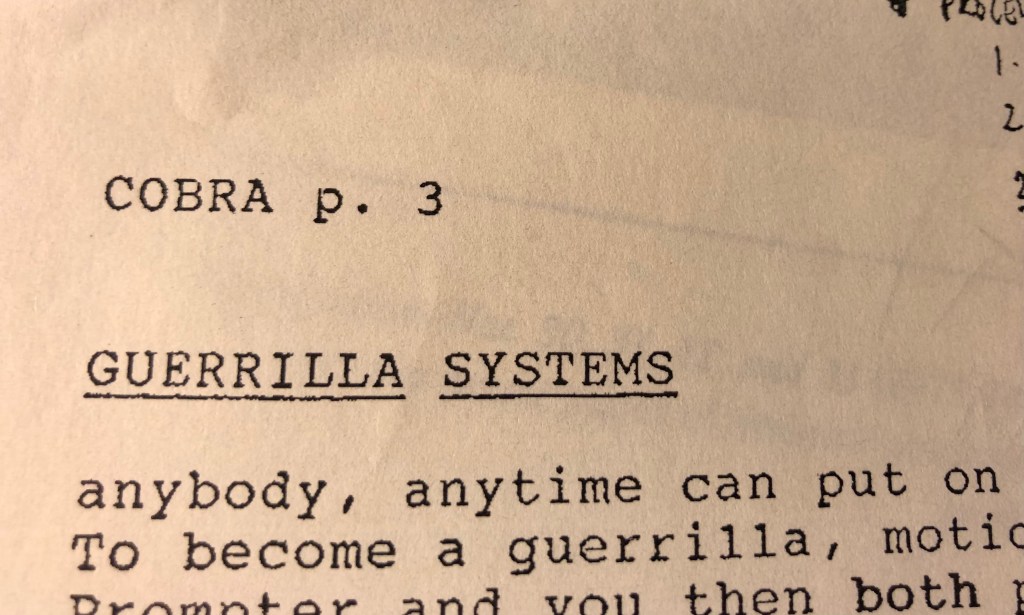

This was brought home to me in vivid fashion when I performed in John Zorn’s game piece Cobra, as he was the visiting composer that first semester. An announcement was posted on the department bulletin board asking for volunteers and I was the only one to sign up. The list was taken down, favors were called in. Consequently my name was left off the program. I tried banjo and electric bass. Not sure which one won out. I had no idea what I was doing. It was like learning how to drive a stick shift. Give it gas, let out the clutch, and the engine stalls. A perfect introduction to experimental music.

In my first year ( ’89-’90 ) there was a big controversy on campus (well, at least in the Music department) because a beloved professor of African-American music studies had passed away and thus the position needed to be filled.1 The gist of the argument was that the replacement needed to be a tenured professor with a Ph.D.

Enter Professor Anthony Braxton. At that time he was teaching at Mills College in Oakland CA. In the fall or winter (’89-90 ) he came with his trio to give a concert, and maybe to be interviewed for the job at Wesleyan. Not that I knew much about it at the time, but it seemed a good choice all around. My impression from being around Professor Braxton after he accepted the job was that a big draw for him was in being on the East coast ( he was originally from Chicago ) as well as an hour and a half ride from New York City. The Wesleyan Music Department was known for its connection with John Cage and Professor Alvin Lucier, so it also appeared that here would be a great meeting of the experimental world expressed by Cage/Lucier with the Tri-Axium world of Professor Braxton.

One of the pieces Braxton played was a composition by Lucier titled Carbon Copies, a trio commissioned by the Challenge ensemble—saxophonist Anthony Braxton, pianist David Rosenboom and percussionist William Winant.2 An explanation of the work:

Me, coming from the fast developing MIDI landscape of the late 1980’s, and bringing an expertise in having recorded underscore for a few local industrial television producers, and having played in a couple of bands that went nowhere, I was eager to explore a different path forward. Thus I paid close attention to a conversation that took place at the reception ( in the basement of the World Music Hall?) after the Challenge performance.

The conversation, which I remember from thirty years ago, went exactly like this, sort of:

Professor Lucier: I really enjoyed your improvisation on Carbon Copies.

Professor Braxton: I tried to play what I thought the composition demanded.

Professor Lucier: I’m not sure I follow, you were free to improvise whatever you wanted.

Professor Braxton: I did just that, I played music befitting your composition.

Professor Lucier: You were supposed to be improvising your music!

Professor Braxton: But I wasn’t playing my music, I was playing your music!

I could have left Wesleyan that night and never looked back. Profound expressions of musical practice! Such bold, stubborn minds!

Whose music are we ever playing?

If my name isn’t on the program, did I even play?

1 Oddly, I cannot find his name, and in an article on the history of African-American studies at Wesleyan there is not one mention of that professor or even the one who replaced him— MacArthur Grant recipient Anthony Braxton. Local music doesn’t necessarily have meaning to everyone. http://magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2019/05/20/a-brief-representative-history-of-african-american-studies-at-wesleyan/

2 Premiered at Challenge’s inaugural concert on April 1, 1989, at Mills College, Oakland, California.