-from “InformationTheory” Raisbeck pg3

Piano.

When I was in ninth grade my music teacher took me to see Vladimir Horowitz at Woolsey Hall in New Haven, Connecticut. This would have been 1964. I was fourteen. My own repertoire consisted of Chopin Waltz in C# minor, Mozart Sonata in C, a piece by a Scottish composer whose name I forget, among many other pieces and exercises lost to time.

At the concert we had orchestra seats pretty far back, so far back that I remember the overhang of the balcony, and in fact I could barely see over the heads of the people in front of me. The piano was center stage, with the keyboard on the left. All I could really make of Horowitz was his etched profile and wispy hair, too far away to see any facial expressions.

I remember nothing of the pieces performed, his entrances and exits, whether there were encores, not even the trip coming or going. What I do remember, that I keep as clear as any memory I have, is a moment when I experienced this sensation of hearing notes in a high register, above the treble staff for sure, that astounded me in their brilliant certainty. These notes could have been animated by Disney cartoonists they were so distinct and playful and iridescent. These dancing pitches carried no weight, no broadness, just a tiny clarity that enthralled me like looking at stars on a dark, frigid night in December. I fidgeted in the back of the hall knee-deep in a thicket of adults packed in like cattails, fighting the urge to stand up and shout. With all the practice and struggle I personally experienced on a daily basis with my own assigned pieces, here was a master at work.

I have this tendency to personalize relationships with people I admire whom I’ve never met. Riding home with my piano teacher I made a joke that “Vlad” played pretty well the pieces he had been assigned by his music teacher— to which she responded with that look I knew so well from her, a look that was not going to dignify my idiot teen bonhomie with a response.

Besides the sheer magic of this youthful moment of my listening development, the question still remains: how could this happen? Not the fact that I went to a concert as a fourteen-year-old with his piano teacher who was in her late thirties, just the two of us. Nor my teacher’s stoic response to my bad joke. No— what circumstances prevailed under which my perception was so jolted as to imprint such an everlasting audio memory whose catalyst was perhaps at most ten seconds of music?

First, let’s look at a bit of acoustics. For example, take the pitches between C6 and C7. The frequencies are 1046 Hz to 2093 Hz, given A= 440 Hz. If the pitches were indeed between these frequencies, there were many important properties at work. The higher range of the notes would give them a stronger sense of directionality. Meaning, simply put, they would have called my attention back toward the piano itself, a bit like hearing a bird-call and searching the trees for its source. You may not know exactly where it is coming from, but you are sure of its general location. The property guiding this is that the closer that a particular sound wavelength is to the length of the object that produces it, the more readily our ears can decipher where the sound is coming from.

For instance, given the formula for wavelength

𝝺 = v/f

with

v = 1125.33 ft/sec

f = 2093Hz ( the note C7 )

the wavelength 𝝺 is about 6 inches long. This is pretty close to the actual speaking length of the strings tuned to C7. As the pitches descend, their wavelengths get a lot longer, so that the wavelength of the lowest note

f = 27.5Hz ( the note A0 )

is approximately forty feet, long enough to tell you the piano sound is coming from somewhere on the stage. Good to know.

There are several aspects of the Horowitz repertoire that are important to this discussion. The entire pitch range of the piano was put into play. The sustain pedal would have gotten a workout. Breakneck arpeggios, clearly defined inner voices, instantaneous changes in dynamics, all these as well. But with the sold-out theatre ( that you can be assured of ), my seat, both visually and acoustically, would have been among the worst. A relative term, as I lucky to have had a ticket at all even if I didn’t know it at the time.

The overhang, the surrounding bodies, and the lack of visual clarity all would have reduced several important aspects of the listening experience. Much of the secondary sound wave reflections that define a hall’s acoustic mark, that particular combination of seat arrangement and architectural design, would have been dampened both by the overhang as well as the sound absorbing bodies, plus, without the the support of visual confirmation, a continued attention to the alive-ness of the concert was challenged.

The result is that my listening would have been radically influenced by the direct sound, that is, the initial burst of sound produced by the musician. This sound is very quickly followed by early reflections, reflections of the direct sound which reach the ear within thousands of a second after the direct sound. The ear will hear both the direct sound and early reflections as if they arrived simultaneously, reinforcing the directionality of the source. Since I was sitting in quite a muffled space, much of the early sounds would have dispersed, the later reflections substantially quieted and as I was sitting about as far away from the source as one could get, direct sound only would have provided the clearest reception.

Consequently, notes played below, say C5, especially blocks of notes, whether scalar, chordal, or in arpeggio, would have lost valuable harmonic and non-harmonic directionality by the time it reached me. And in directionality lies attention.

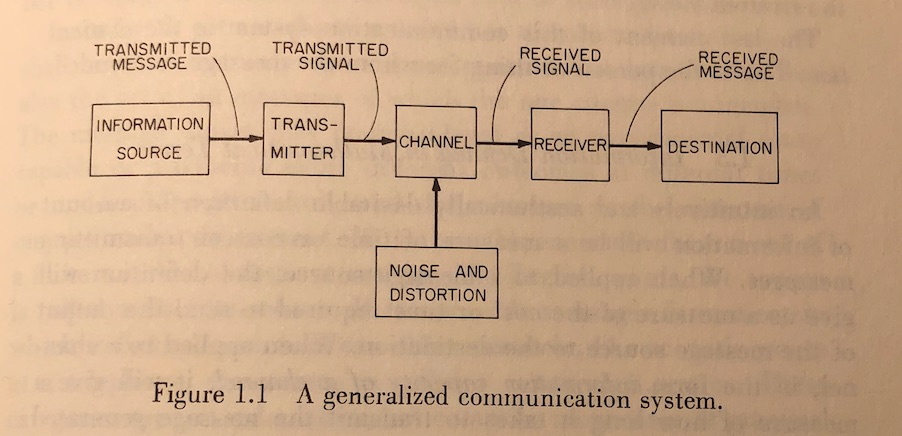

But is this getting at the real question here? To quote a treatise on information theory:

“Information is not so much a property of an individual message as it is a property of the whole experimental situation which produces the messages.”

You see, I think what was happening was this: The Horowitz transmission was an onslaught of technique and audacious bravado, if such an entity can be measured. The information contained in his playing was so far beyond my comprehension that the only passage that remained to me was the one closest to my own experience, a recognizable motif – one that I might have actually technically tried to emulate, however rudementary. The rest was like a thunderstorm— wind battered, lightning struck— rumble in the distance— essentially incomprehensible.

How this entered my teenage synapses, my catalogue of retrievable memory, perhaps the best explanation is in the simple element of surprise. To quote information theory again:

“The message source may be considered as an experimental setup capable of producing many different outcomes at different times or under different stimuli, and the messages as the outcome of one particular experiment.”

Perhaps listening isn’t dependent on acoustics, it’s dependent on what band-width we’re listening on, what the listener is listening for, rather than to. It’s as if, in that one moment, Horowitz played a phrase that so resonated sympathetically with my young naive antennae, in crystal clear, magical clarity that it permanently altered brain neurons I didn’t know I possessed. Everything else of his playing was outside the bounds of my information set.

Perhaps it was simply music theory at work— Horowitz doing his job, pressing his fingers to the keys, bringing out the passages as the music commanded, aware of what lay ahead, yet unconcerned with anything other than entering a world, for a fleeting moment, that he alone inhabited.

For a more romantic interpretation, perhaps it was the notes Horowitz wanted me to hear.

None of this detracts from the memory. It’s a fallacy that analysis destroys significance or inherent meaning. If anything it shows how many stars had to be aligned for it to have occurred at all. The essential still holds its mystery.

Referenced books:

“The Science of Sound” by Thomas D. Rossing (2nd edition) Addison-Wesley 1990

“Information Theory” by Gordon Raisbeck MIT Press 1965

“Information Theory” by John F Young Butterworth&Co 1971